THEMATIQUES

Politic

Landscape

Urbanplanning

Transdisciplinarity

Research

ANNEE

2023

Shifting priorities : planning for soils

As part of RIOT studio. In collaboration with Yasmine Sefraoui and Nora Guigues. Stop Building ! The case of Lausanne

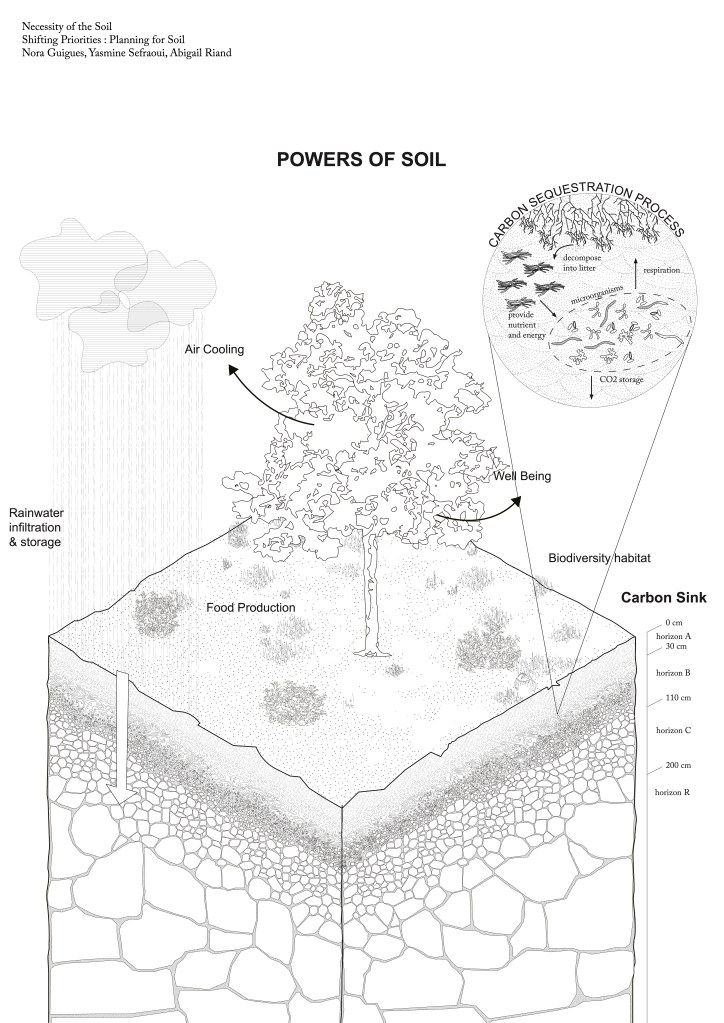

Humankind has become a major geological force, transforming soils and disturbing ecosystems. However, a comprehensive and coherent consideration of soil has been lacking until now. Yet soil health is essential for the well-being of the planet and its inhabitants: it provides drinking water, is the basis for food production protects against flooding, serves as a natural habitat for countless organisms and is a carbon sink. Soil is therefore not only a physical support of the human habitat. Planning for 30’000 people requires a deep comprehension of our ecosystem and more precisely of the functions of our soils. To accomplish this, the planning of our soils has to be thought not only on their surface, but especially in their depth. In view of current climate change, concrete changes must be made now. Although discussions are being held, such as the Paris agreements, we can see that we’re heading for a wall.

By prioritizing soil health, we can contribute to a better climate and help achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. How can we change planning priorities, despite Lausanne’s growth, to preserve and maintain urban soils?

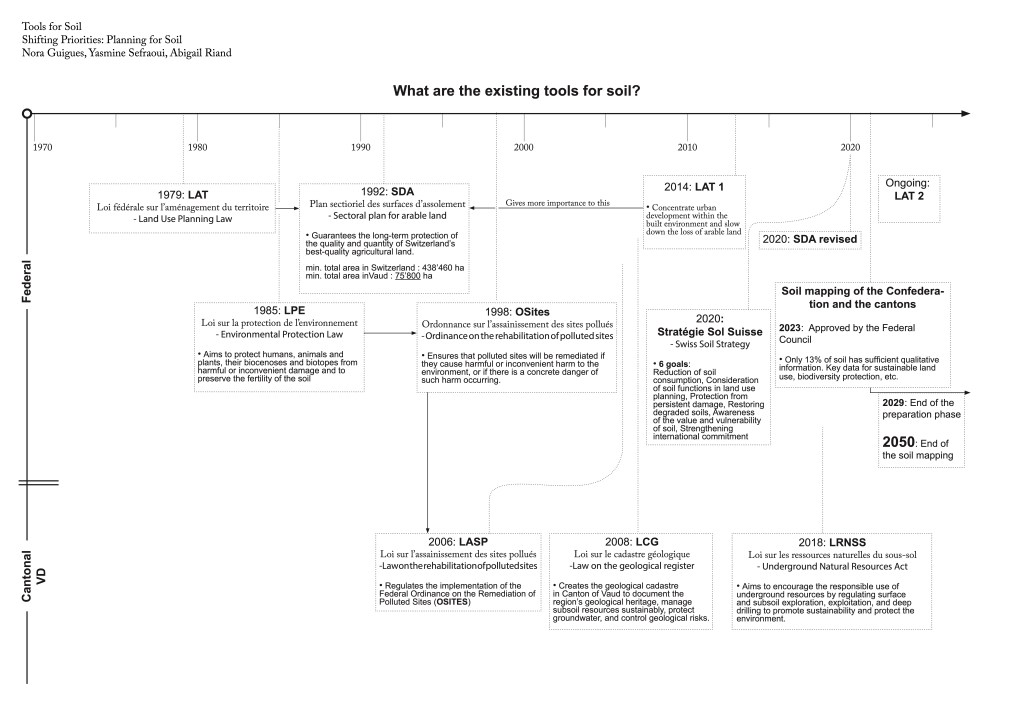

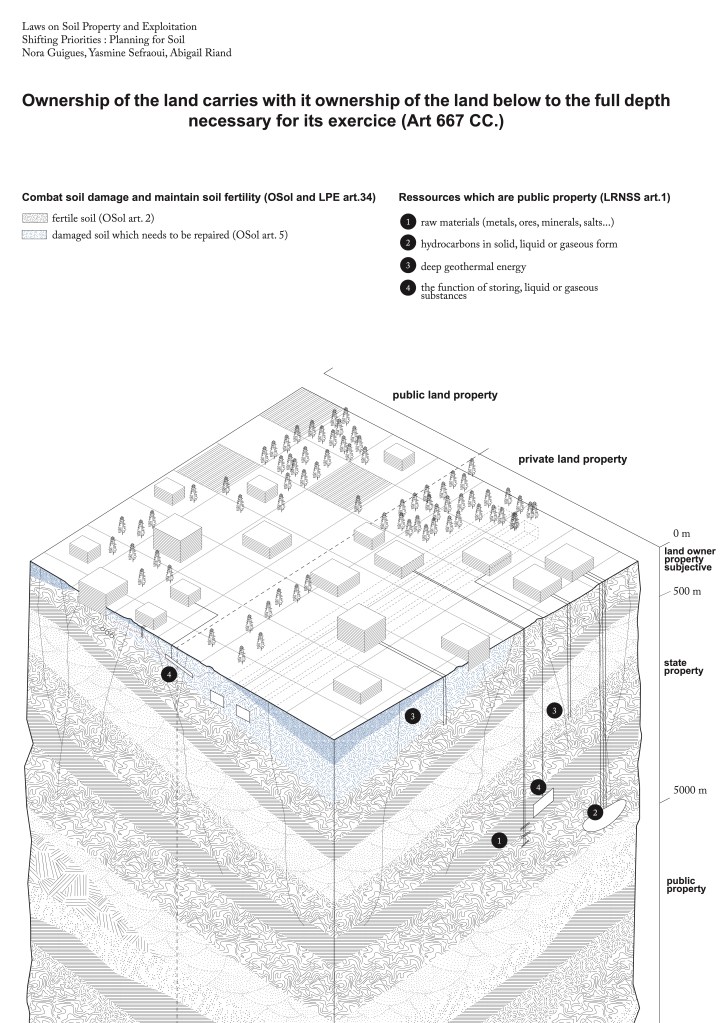

It is only recently that soil has started to have a small importance in planning in Switzerland. First of all, ownership of the land carries with it ownership of the soil to the

full depth necessary for the exercice of the rights of property. The State of the Canton then regulates and limits property through policies. One of the major laws regulating the exploitation of the subsoil is the law on the natural resources in the subsoil. It identifies resources which are too important to be owned by a private entity and gives them to the State. Some laws exist to protect the soil but it is still regarded as a support for human interests. The use of the subsoil is therefore of growing interest as it has great potential for energy production.

On the one hand, the revision of the LAT in 2014 concentrates urban development in built-up areas to protect arable land. Also, the revised law on sectoral plans for arable land promises to protect the quality and quantity of arable land in Switzerland, making it almost impossible to make arable land into a building zone. On the other hand, the climate plan asks to make cities more pleasant by adding green spaces. The same question arises again: how, with the growth of the population, should we densify cities while preserving land/soil within them?

It is a new planning that must be thought. We need to start implementing a legal framework so the soil is cared for, protected and so planned. We need to start thinking of a way to plan and build for green spaces and so soil. We need to add and control quantity and quality factors to the planification of soils.

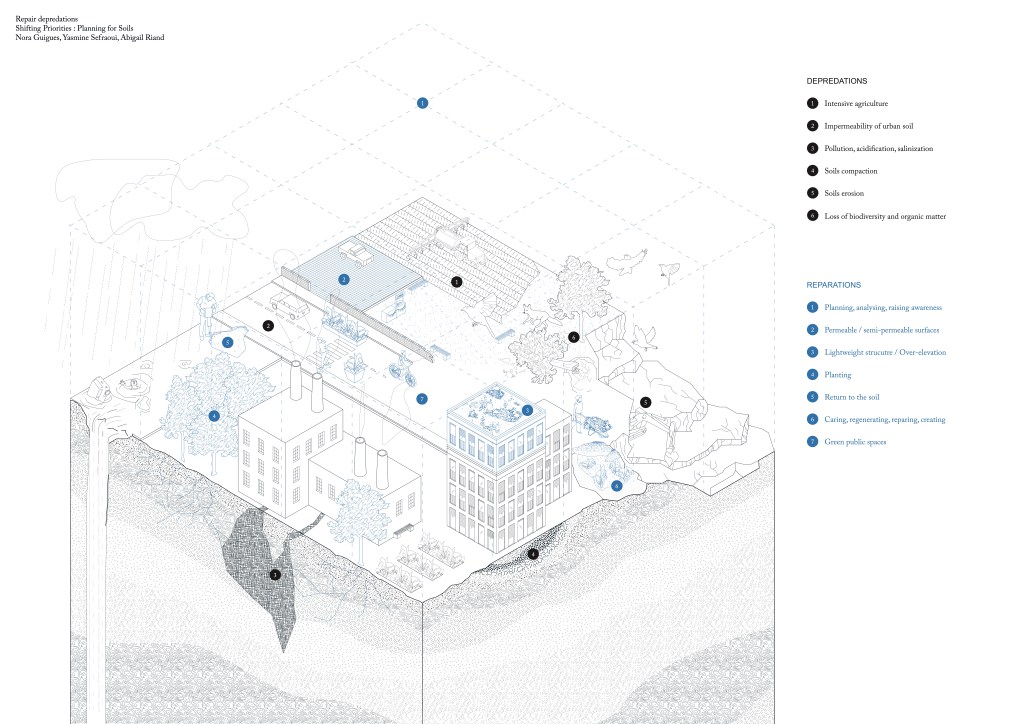

Soils in Switzerland are undergoing slow and continuous degradation : a steady increase in the amount of sealed surfaces, soil depletion due to erosion and loss of organic matter, and the loss of certain soil functions due to compaction, acidification, eutrophication, salinization and soil pollution.

To counteract these trends and preserve the regulatory, productive and habitat functions of soil, various strategies must be implemented and thought through in the long term. These include the reduction of soil consumption, the consideration of soil functions in spatial planning, the protection of soils against persistent damage, the restoration of degraded soils, the raising of awareness of the value and vulnerability of soil and the strengthening of local commitment.

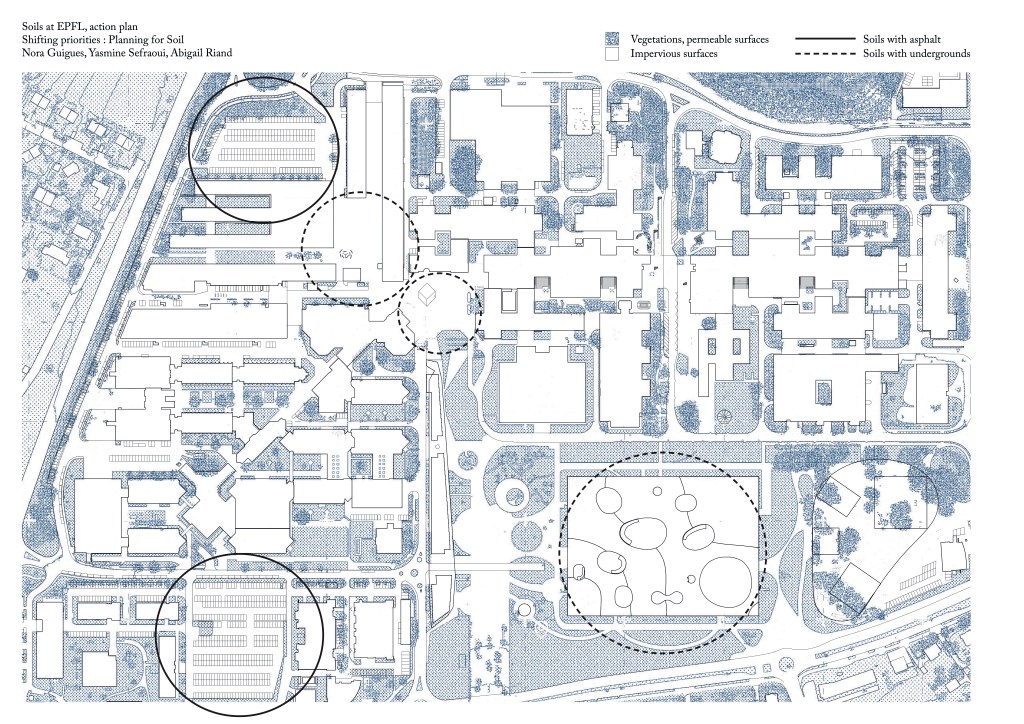

For our study case we chose the EPFL campus as a microcosm as it develops on federal land. EPFL develops climate strategies to address future ecosystem issues, but soil planning is still largely secondary. Among all EPFL soils, we distinguished two types on campus that would either need to be preserved, restored or even re-created.

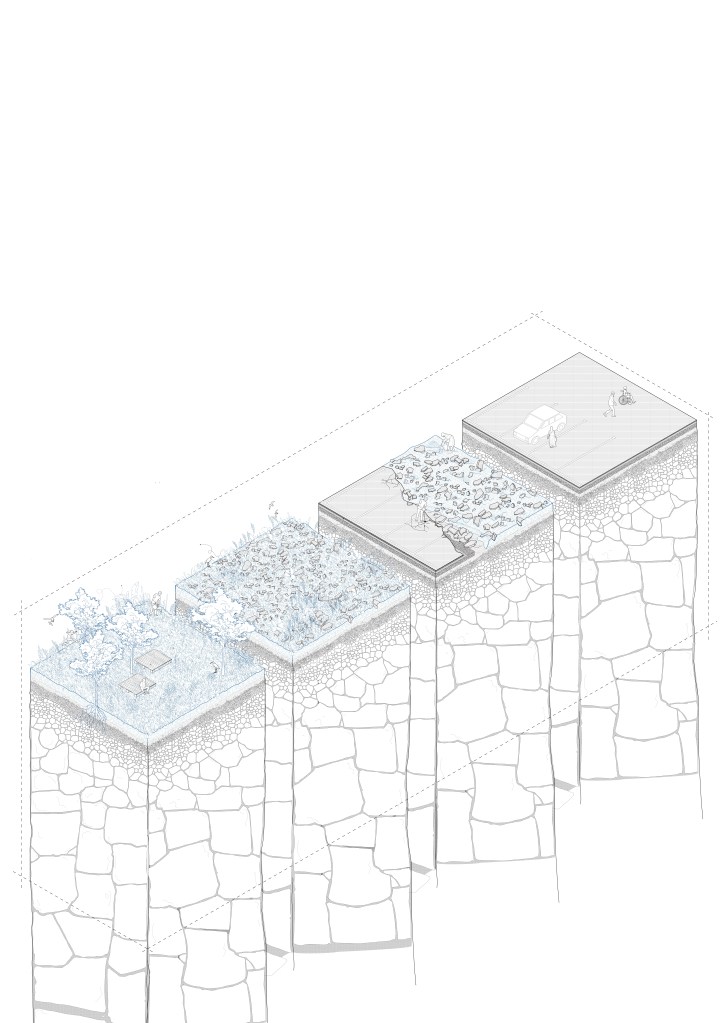

We intervene on those two types of sealed surfaces: asphalt surface and built surface. In these two cases, the soil is almost nonexistent and needs to be recreated. A functional soil takes around 5’000 years to regenerate itself. To respond to that harsh reality and recreate soil in the short term, we

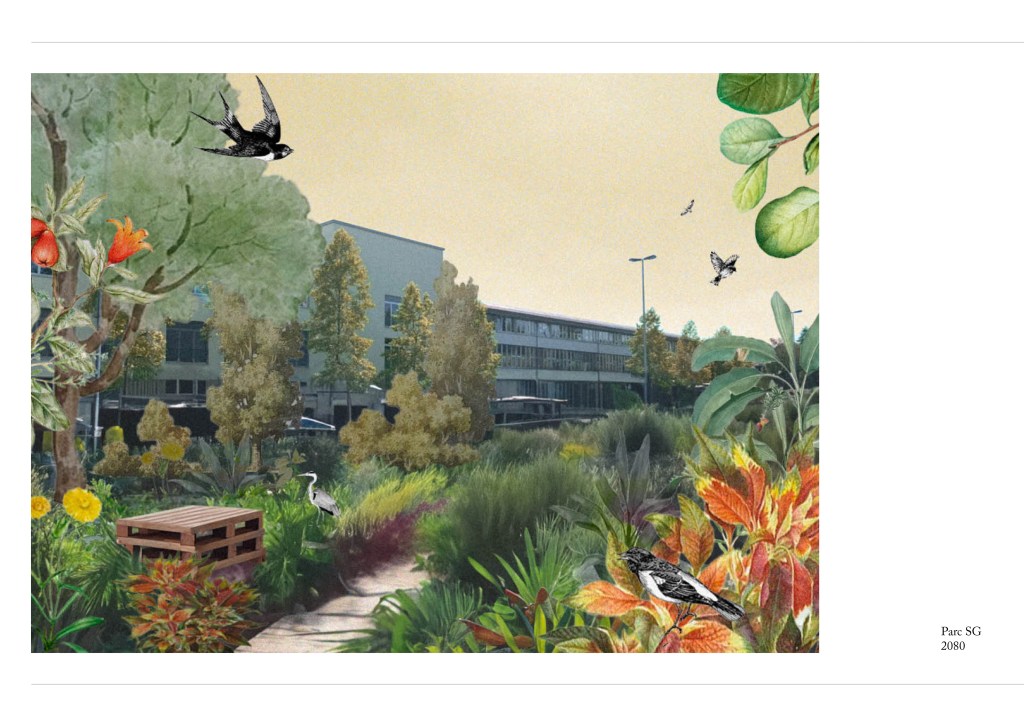

chose to focus on two neglected sites on the EPFL campus on which strategies have been imagined to recreate soil until 2080.

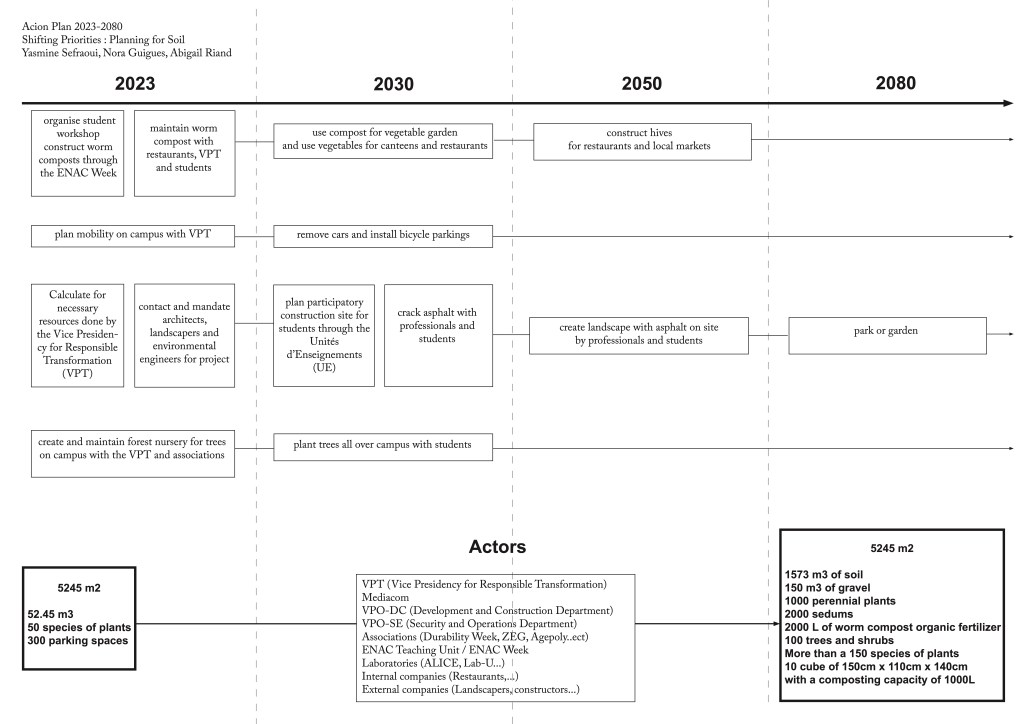

To achieve this re-greening of the EPFL campus, we established an action plan where a circular circuit is created between different actors : students, professors, the direction of responsible transition of EPFL and local constructors ect.

This work should start to be done now at EPFL for a projection in the next years.

The first step, starting today, would be the calculation of the proportion of resources needed, the number of students eating on campus and how much compost this will create, how long it will take to be functional etc.

The second step, is recreating the soil on the parking lot by first breaking completely the asphalt and then mix the unhealthy, compacted soil with a recreated soil composed and formed by worm composting. The worm compost would be made and maintained on site by using the waste from EPFL canteens and restaurants.

Lastly, we would demolish some of the place in front of the architecture building to allow plants to develop fully in terms of height after recreating the soil by mixing fertile substrate mixed with mineral material. Those would be recovered from excavations in the area/on site to create a functional soil. From those two case studies, we can then repeat these interventions on the rest of the EPFL where we find the same types of soils, which are therefore non-existent.

To conclude, our research project tackles the problematic of the importance of the soil in the planning of the growing campus of EPFL and even more of Lausanne. By planning for the soils, we take care not only for humans but also non-humans.

Giving our soils a place in the planning process means considering this rare resource that is crucial to all life on earth. However, a comprehensive and coherent consideration of soil has been lacking until now and this needs to change.

To plan a liveable, fertile soil is to respond to the climatic challenges, and indirectly to the demographic growth of EPFL and Lausanne. The planning of 30,000 people cannot be dissociated from the planning of the soil.